“The fastest dentist in the world” – Climate Online

By Dan Brown

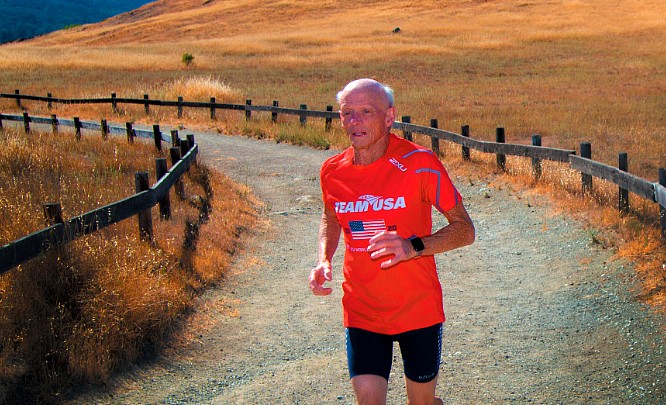

One of the benefits of being an Age Group Warrior, as described by Dr. Robert Plant, is that the calendar resets every few years. Next year, Plant will be 80 years old. As a triathlete, he can’t wait to feel young again.

“I’m going to be the baby of the group,” he laughs. It will be an advantage. At Plant’s age, it’s usually the younger athletes who get the upper hand, especially in a sport that requires 139 miles of swimming, biking and running combined.

For now, he is having a very hard time pushing back some of the brave youngsters at the bottom of his 75-79 age group. Sheesh – kids these days.

Still, Plant remains hard to catch for just about anyone. The longtime Redwood City dentist is constantly on the move, whether it’s swimming, biking and running, or brushing, flossing and drilling. Either way, his stamina is mind-boggling (this is his 51st year as a dentist).

All in all, he ended up with a career for the ages, especially in his sport. Plant, who made a late start as a triathlete, will be inducted into the American Triathlon Hall of Fame at a gala in Milwaukee on Aug. 4.

Plant’s resume by age group includes seven national triathlon championships. He also won two titles in 2018: the famous Ironman triathlon in Kona, Hawaii, and the triathlon world championship in Australia.

Scarcely believe it

“I didn’t quite accept it at first,” the modest Plant says of his Hall of Fame selection. “But then all my buddies were like, ‘You deserve it, blah, blah, blah.

“So, I finally accepted. And I finally kind of embraced it. I’m just glad it wasn’t a posthumous award.

This year’s four-member induction class includes two multiple-time Olympians (Gwen Jorgensen and Laura Bennett) and two athletes who did their best after earning their AARP cards (Plant and Lesley Cens-McDowelllof Pennsylvania, 76 ). But the coronation should not be confused with a finish line. Plant is probably training right now. Maybe he’s riding hilly miles at Sawyer Camp, biking along Cañada Road, or swimming at one of the three fitness clubs he belongs to. Triathletes in the 80-84 category should consider themselves warned.

Gain the respect of other athletes

On a flight home from an Ironman Championship in Kona a year ago, Plant sat next to another competitor with long-standing ties to the Peninsula, someone also known for his day job. But Plant didn’t know it when he saw his hyperkinetic teammate shake his foot up and down, stretch from his seat, and press his foot down on the armrest.

Plant eventually showed up and learned it was Redwood City native Eric Byrnes, the former Oakland A outfielder turned endurance athlete. And just like that, a society of mutual admiration was born.

“Bob is a great guy and an amazing triathlete,” Byrnes replied via email when asked to confirm the story. “He’s the fastest dentist in the world.”

Born in 1943, Plant grew up in Redwood City and attended Our Lady of Mount Carmel High School and Serra High School in San Mateo. At the time, his hometown had the derisive nickname “Deadwood City”. Plant said there wasn’t much for bored teenagers to do except “ride around El Camino in your hot rod, when gas was 25 cents a gallon.”

Over time, Plant discovered that he didn’t need a sports car to go fast. He competed in track and field at San Jose State during the so-called “Speed City” era under coach Bud Winters.

—

This story first appeared in the August issue of Climate Magazine

—

Plant ran alongside future Olympians Tommie Smith and John Carlos, best known for their Black Power salutes in the medal stand at the 1968 Games in Mexico City. Plant remembers a funny anecdote; he says the reason Smith and Carlos raised a gloved fist each is that they forgot the second pair of gloves at the hotel and had to share.

Plant started out at SJSU as a long jumper (the event was called the long jump back then) before shin splints forced him to convert to the quarter mile (now the 400 meters) .

“And I wasn’t ranked very high in the team,” he said. Even so, Plant was once able to replace Smith at the anchor position for the mile relay.

“It shocked me,” he says. “I was so excited, man, because Tommie had an ingrown toenail and he couldn’t run. So the coach came up to me and was like, ‘Hey Bob! I had never practiced passing the baton.

“And when the third guy came, I just exploded. I almost crossed the boundary line, the passing zone. And it was the fastest race of my life, and we won.

Discover a new sport

The plant just went on. After college, he competed in recreational 10Ks and ran marathons. In his early 40s, he clocked a personal best 2 hours and 41 minutes in the Boston Marathon. That’s an impressive 6 minutes and 9 seconds for every kilometer.

His real introduction to triathlon competition came in 1989, when Plant volunteered as a timekeeper at the 1989 Ironman World Championships in Kona. It turned out to be the ultimate catwalk race – an epic duel between two of the sport’s all-time greats.

The battle between longtime rivals Dave Scott and Mark Allen became known as the “Iron War”. For more than eight hours, the duo ran side by side at a record pace. After 2.4 miles of swimming, 112 miles of biking and 26.2 miles of running (a full marathon), Allen broke the tape just 58 seconds ahead of Scott.

“I was at the finish line and I was so excited,” Plant said. “I was like, ‘Wow, I gotta’ do this race.'”

Getting used to it took work. Yes, he could run. Yes, that cardiovascular training and leg strength carried over to cycling.

But Plant didn’t take like a fish to water.

“Basically with swimming,” he says, “I was like a rock with arms.”

In this discipline, he had to learn that technical precision with every shot was at least as important as physical form. This became clear as Plant watched much older and much taller swimmers slide past him during his practice laps.

“I was looking at these ladies and thinking, ‘Man, they’re just kicking my ass,'” Plant laughs. nowhere !

Eventually he figured it out, even though swimming still ranks last on his list of triathlon skills. Nonetheless, he says he usually finishes near the top of his age group in all three stages.

When he won the Ironman World Championship for his age group in 2018, he set a 75-79 class record by finishing in 13 hours, 6 minutes and 3 seconds. How dominant was it? Fidel Rotondaro of Venezuela, his closest competitor, finished 30 minutes and 52 seconds behind.

“It’s just about hanging on mentally, breaking down the barriers and trying to persevere,” he says. “It’s just about having that ‘don’t give up’ attitude, even when the body says, ‘Oh, sorry, I know you don’t want to quit, but we’re not going anywhere. “”

Go, go and go

Competitors everywhere should know that Plant has no plans to stop racing – ever. His best triathlon advice – his “tri” advice – is to simply love him as much as he does.

“I think what really drives the sport is your inner passion,” he says. “It’s not the hype. I think it’s your inner engine.

He races in Abu Dhabi later this year before heading to Egypt for another race.

“I move around a bit,” Plant says with a laugh. “That’s also part of the fun. I go, ‘Oh, where’s the world championship?’ Well, I’ll see if I qualify for that. And I want to go to such and such a place.

Pretty much the only place it won’t travel is ego travel. At his dentist office on Arch Street in Redwood City, his staff had to trick him into bringing his medals and jerseys, which they framed without asking his permission.

While planning his acceptance speech for the Hall of Fame, he notes that he wanted to thank the volunteers and race directors. “Because triathlon is like a family,” he says.

But his modesty will not help him escape the highest honor his sport can bestow. The world’s fastest dentist is about to get his brush with greatness.

Comments are closed.